Difference Between Git Pull and Git Fetch: Key Differences Explained

The real difference between git pull and git fetch boils down to one simple thing: what happens after the changes are downloaded from the remote server.

One command is a two-step process masquerading as a single action, while the other is a safe, non-disruptive way to see what's new. Your choice between them will shape your entire Git workflow, so understanding the distinction is non-negotiable.

Breaking Down The Core Distinction

Think of git fetch as a reconnaissance mission. It connects to the remote repository, grabs all the commits, files, and references you don't have yet, and neatly places them in your remote-tracking branches (like origin/main).

Critically, your local main branch remains completely untouched. This gives you a priceless opportunity to inspect what your team has been working on before you even think about integrating those changes into your own code.

On the other hand, git pull is the all-in-one, automated approach. It performs a git fetch behind the scenes and then immediately tries to git merge the downloaded changes into your current branch. It’s a shortcut, but shortcuts can sometimes lead you into trouble.

The simplest way to frame it is safety versus convenience.git fetchlets you look before you leap.git pulljust leaps for you, which can dump you right into unexpected merge conflicts if you aren't paying close attention.

For a deeper dive into how these commands impact your local repository, the folks at GitKraken have a great guide.

Quick Comparison Git Fetch vs Git Pull

To really nail down the difference, this quick table breaks down how each command behaves. It's a handy cheat sheet for deciding which one you need in the moment.

| Characteristic | Git Fetch | Git Pull |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Action | Downloads remote changes to a separate remote-tracking branch. | Downloads remote changes AND merges them into the current branch. |

| Safety | Safe. It does not modify your local working branches. | Potentially disruptive. Can create merge conflicts immediately. |

| Workflow Impact | Allows for review of changes before merging (git diff, git log). |

Automates the merge process, hiding the review step. |

| Underlying Commands | A single, direct command. | A compound command: git fetch + git merge. |

As you can see, git fetch is all about gathering information without risk, giving you full control over when and how changes are integrated. git pull is about speed, but that speed comes at the cost of control and can sometimes create more work if a messy merge arises.

How Git Fetch Protects Your Local Workspace

Think of git fetch as a quick recon mission for your code. It’s a fundamentally safe command, designed to give you a full picture of what’s happening in the remote repository without actually touching your own work. It’s one-half of what git pull does, but using it alone gives you incredible control.

When you run git fetch, Git phones home to the remote server (usually called origin) and downloads any new commits, files, and branches that have shown up since you last checked.

Here's the critical part: it places all this new data into a special, isolated area of your local repo. These are your remote-tracking branches, like origin/main or origin/feature-xyz. Your actual working branches, like main, remain completely untouched.

The Power of Reviewing First

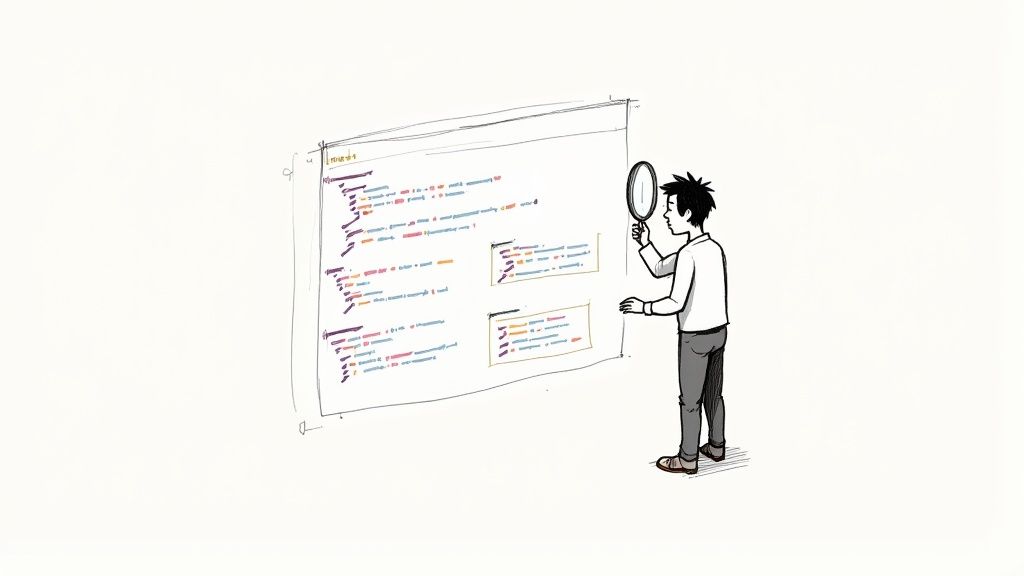

This separation is what makes git fetch so useful. It updates your repository's knowledge of the remote state, creating a read-only copy of what everyone else has done. This lets you inspect incoming changes before you even think about merging them. You can't directly edit origin/main, but you can absolutely analyze it.

For instance, after a fetch, you can run git diff main..origin/main. This command gives you a precise, line-by-line comparison between your local main branch and the latest version on the server. No surprises.

By fetching first, you shift from a reactive to a proactive workflow. You stop asking, "What did git pull just do to my code?" and start asking, "What has the team done, and how do I want to integrate it?"That little review step is invaluable. It helps you spot potential merge conflicts, understand what your teammates were thinking, and decide whether a merge or a rebase is the right move.

What a Fetch Looks Like, Before and After

Let's walk through a simple scenario. Imagine your local main branch is two commits behind the remote origin/main.

Before git fetch:

- Your local

mainpoints to commitA. - Your local

origin/main(your last known state of the remote) also points toA. - The actual remote

mainbranch is ahead, pointing to commitC.

Now, you run git fetch. Your local files don't change at all, but your repository's internal state does.

After git fetch:

- Your local

mainstill points to commitA. Your code is exactly as you left it. - Your

origin/maingets updated and now points to commitC.

Your workspace is completely protected. You now have a perfect, up-to-the-minute reference of the remote (origin/main) and can proceed with a git merge or git rebase only when you're ready. This simple two-step process—fetch, then merge—is a cornerstone of professional, conflict-free collaboration. It’s the difference between blindly accepting changes and making smart, informed updates.

Deconstructing The Git Pull Command

If git fetch is like peeking at what's new on the remote server, git pull is kicking the door down and inviting all the changes in. It’s a powerful shortcut, combining two commands into one for the sake of speed: a git fetch followed immediately by either a git merge or git rebase. This automation is incredibly convenient, but using it without understanding what’s happening under the hood can lead to some real headaches.

When you run a standard git pull, Git first downloads the new data from the remote repository. Without pausing, it then tries to integrate the fetched branch (like origin/main) directly into your current local branch (like main). This immediate, automatic integration is the single biggest difference between git pull and git fetch.

The Default Merge Behavior

By default, git pull uses a merge strategy. If you've made local commits that aren't on the remote branch yet, Git creates a brand-new merge commit. This special commit is unique because it has two parents—one pointing to the last commit on your local branch and the other to the latest commit from the remote branch. It’s Git’s way of neatly tying two different lines of work together.

While this preserves the exact history of both branches, it has a tendency to clutter up your project's commit log, making the development timeline harder to follow. Even worse, if there are conflicting changes between your local work and the remote updates, everything screeches to a halt, and you're dropped right into the middle of a merge conflict.

A standard git pull is an optimistic command. It assumes the integration of remote changes will be straightforward. In a busy, collaborative environment, this optimism can quickly lead to tangled histories and frequent, time-consuming conflict resolution sessions.This is exactly why so many experienced developers will tell you to avoid running a vanilla git pull on shared branches where history can change in a flash.

The Cleaner Alternative: Git Pull Rebase

For developers who crave a clean, linear project history, git pull --rebase is a game-changer. Instead of mashing two histories together with a merge commit, it takes a much more elegant approach:

- It fetches the latest changes from the remote, just like a normal pull.

- Then, it temporarily sets aside your local, un-pushed commits.

- It fast-forwards your branch to the latest remote version.

- Finally, it re-applies your local commits, one by one, on top of the updated branch.

The end result is a straight-line history that’s incredibly easy to read. It looks like you did all your work after the latest remote changes were pulled down, even if that’s not chronologically true. This completely sidesteps those extra merge commits.

You can even tell Git to make this your default behavior with git config --global pull.rebase true. While this approach can still run into conflicts, you often resolve them commit-by-commit, which many find more manageable. The key takeaway is that git pull isn't a one-trick pony—it’s a flexible tool whose behavior you can, and should, control.

Choosing The Right Command In Real-World Scenarios

Knowing the technical difference between git pull and git fetch is one thing. Knowing which one to use when you're deep in a project is something else entirely. The right choice often comes down to your immediate goal, how many people are working on the branch, and frankly, your tolerance for surprises.

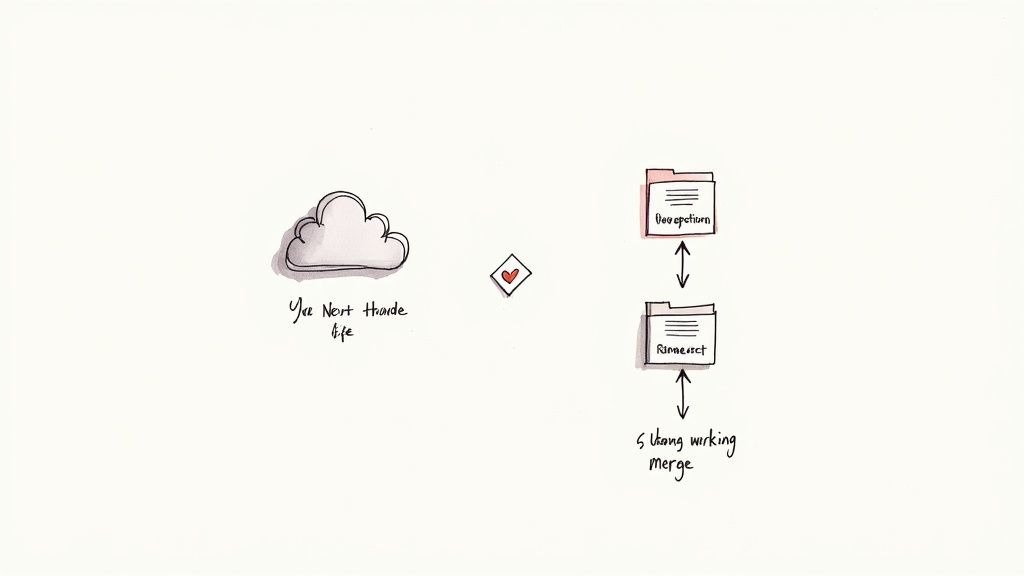

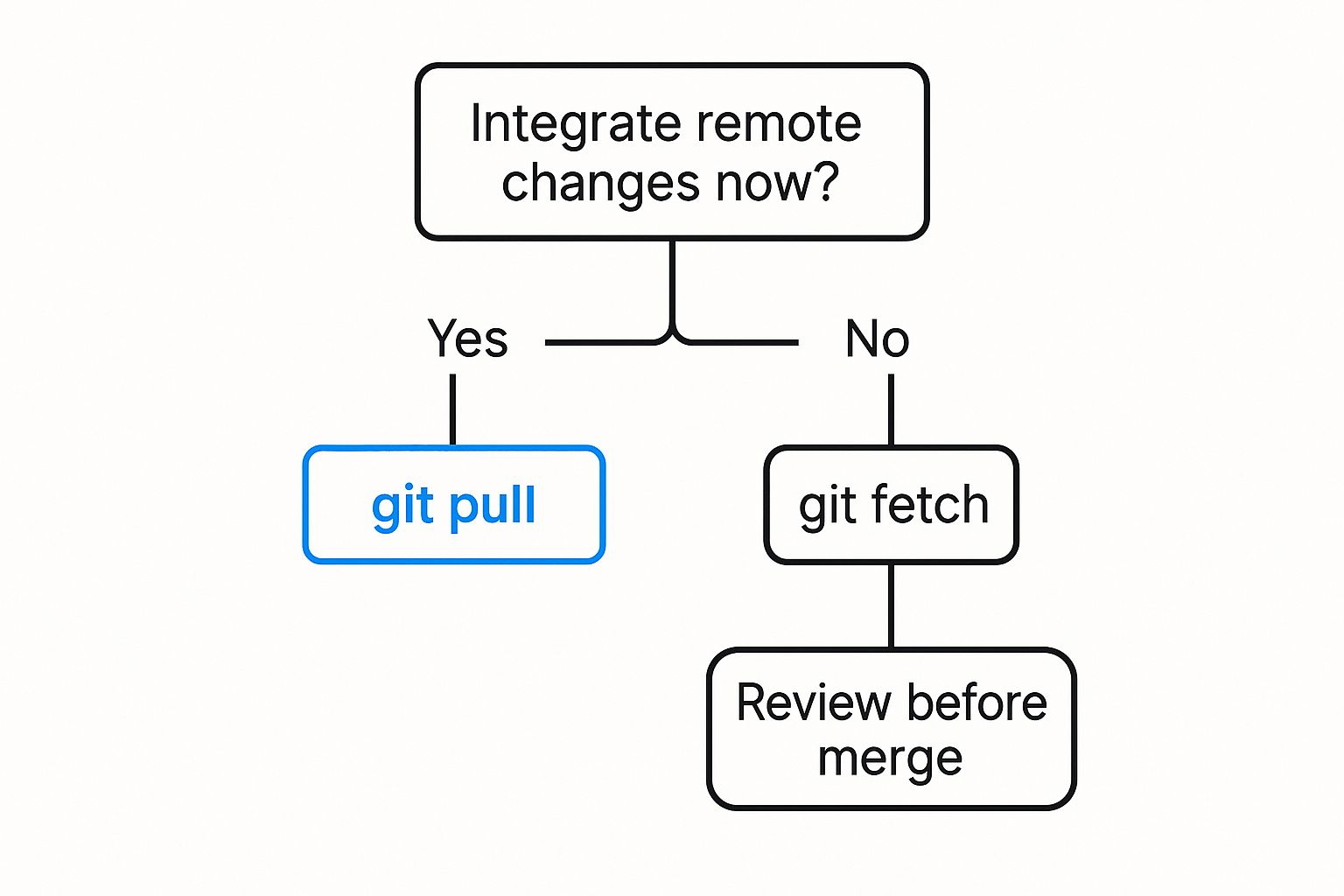

Making the right call in context is what keeps your workflow smooth and free of conflicts. The core question is simple: do you need to integrate remote changes right now, or do you want to look at them first?

As you can see, your path diverges based on that need for an immediate merge. This little decision point guides you to the command that fits the job.

When To Safely Use Git Pull

Despite its reputation for causing trouble, git pull has its moments. In specific, low-risk situations, its speed is a genuine advantage. Think of it as the express lane for syncing your code.

- Starting Your Day: First thing in the morning, your local

mainordevelopbranch is almost certainly out of date. A quickgit pullis usually a safe and fast way to catch up on the team's latest work before you branch off to start your own. - Working on a Solo Branch: If you’re the only person pushing commits to a feature branch,

git pullis perfectly fine. There’s no risk of unexpected merge conflicts because nobody else is changing the upstream version.

But that convenience has a real cost. In distributed teams, git pull operations can trigger merge conflicts in 15-20% of cases on a typical codebase.

When To Prefer Git Fetch

For pretty much every other scenario, git fetch is your best friend. It gives you control and situational awareness, making it the professional standard in collaborative or sensitive projects where stability is everything.

The entire philosophy of git fetch is to separate downloading changes from integrating them. That simple separation is your single best defense against broken code and messy merge conflicts.Here are the times when fetch is the clear winner:

- Syncing a Shared Branch: Any time multiple developers are pushing to the same branch (like

mainor a shared feature branch), always usegit fetch. It lets you review their changes with a command likegit diff origin/mainbefore you decide how to merge them into your work. - Pulling in Upstream Changes: You're deep into a feature and need to sync up with the latest from

main. Agit fetchfollowed by agit rebase origin/mainis the clean, professional way to keep your branch current without creating ugly merge commits. - Before a Code Review: Fetching the latest changes right before you ask for a review ensures you have the most recent context from the repository. It helps you catch potential integration problems before your teammates do.

Teams that adopt a fetch-first workflow have seen a 30-40% drop in disruptions caused by merge conflicts. And if a pull or merge ever goes sideways, knowing how to reset a Git branch to the remote head is an invaluable recovery skill.

Ultimately, the choice between git pull and git fetch is a choice between automated convenience and deliberate control.

The Design Philosophy Behind Fetch and Pull

Ever wonder why Git has two separate commands for what seems like one job? Why have both git pull and git fetch? It wasn't an accident or a lazy design choice; it was a deliberate decision born from Git's origins with the Linux kernel project—a massive, decentralized beast with thousands of developers. For a project that big, an asynchronous and non-disruptive workflow wasn’t a luxury, it was an absolute necessity for survival.

That bit of history really puts git fetch into perspective. The command was built to give developers a crystal-clear view of remote changes without messing with their local work. This was a cornerstone for the Linux kernel, where a contributor had to meticulously review incoming patches before even thinking about merging them. You can see how this philosophy still shapes modern development in our guide to Git workflow best practices.

This separation of concerns—downloading versus integrating—is the core philosophy. git fetch is all about safely gathering information. The actual integration is left to a separate command, like git merge or git rebase. This two-step process forces a crucial moment of review.

A Deliberate Choice for Stability

Having both commands is a testament to Git's commitment to control and intentionality. Think of git fetch as the cautious, methodical approach. It gives you the power to inspect, compare, and truly understand remote work before it ever touches your own code. You can see who changed what and then decide on the best way to bring those changes in.

The fetch/merge separation isn't a bug; it's a feature. It is Git's way of encouraging a workflow where developers pause and think, rather than blindly syncing and hoping for the best. This design prevents accidental disruptions and maintains a clean, understandable project history.

So where does git pull fit in? It was created as a shortcut, a convenience for simpler, more linear workflows where the risk of conflict is low. It automates the fetch-then-merge sequence to save time. But that convenience comes at a cost—it bypasses that critical review step, which is why it can be a risky move in complex, collaborative projects.

The Impact on Modern Development

This foundational design is still incredibly relevant today. Dig into repository data from major open-source projects, and you’ll find that git fetch commands outnumber git pull by a margin of roughly 60-40 during development cycles that prioritize stable integration. That statistic really highlights the value of the "look before you leap" approach that git fetch enables.

Ultimately, understanding this design philosophy helps you see git fetch not as an extra, annoying step, but as a professional tool for managing risk. It’s about giving you—the developer—the final say on how and when external changes affect your local workspace. That’s a principle that remains vital for building solid, robust software.

Common Questions About Git Fetch and Pull

Even when you know the difference between git pull and git fetch, some practical questions always seem to pop up in the day-to-day grind. Let's tackle some of the most common points of confusion to help you solidify your Git workflow and build better habits.

Answering these questions moves the conversation from theory into the real world, helping you make smarter decisions based on your situation.

When Is It Actually Safe to Use Git Pull

Look, while git fetch is almost always the safer bet, git pull isn't some evil command you should never touch. It's a tool, and like any tool, it's perfect for specific, low-risk situations. Its convenience is hard to beat when you’re the only person working on a feature branch—there's simply no risk of running into someone else's conflicting changes.

It’s also pretty safe when you know for a fact that your local branch has no new commits compared to the remote. Think about when you first clone a repository or when you’re just starting your day by syncing up with the main branch. In those cases, a quick git pull is an efficient shortcut.

But on any active, shared branch? The smart move is always to use git fetch first. This lets you see what’s coming down the pipeline before you decide how to integrate it.

What Do I Do If Git Pull Causes a Merge Conflict

It happens to everyone. You run git pull, and your terminal explodes with messages about a merge conflict. When this happens, Git hits the pause button on the merge process and flags the files that are causing the trouble. Now, it's your turn to step in and resolve the mess.

You'll need to open each conflicted file and look for the conflict markers (<<<<<<<, =======, >>>>>>>). These markers neatly fence off the competing code—one version from your local changes and the other from the remote. Your job is to play editor, decide what the final, correct version should be, and then delete the markers.

A merge conflict isn't an error. It's just Git's way of saying, "I have no idea how to combine these two things, so I need a human to make the final call."

Once you’ve saved your changes, you stage the resolved files with git add and then seal the deal with git commit. If you ever feel in over your head, you can hit the eject button by running git merge --abort. For a deeper dive, our guide on how to resolve Git merge conflicts has a full walkthrough.

Can I Make Git Pull Default to Rebase

Absolutely. If you’re a fan of a clean, linear commit history, setting git pull to default to a rebase strategy is a popular move. Instead of creating a messy merge commit, this approach takes your local commits and neatly replays them on top of the changes you just fetched.

You can do this for a one-off operation by running git pull --rebase. To make this your default behavior, just run this global configuration command: git config --global pull.rebase true.

This simple command tells Git to always favor rebasing when you use git pull, which is a great way to keep your project history clean and readable without having to think about it.

At Mergify, we build tools that eliminate the friction in your development workflow. Our Merge Queue and CI Insights features are designed to automate pull request updates, reduce CI costs, and give developers back their most valuable resource time. Discover how Mergify can streamline your code integration process.